The Hermitage Museum

It was a cold and rainy day in Saint Petersburg, not uncommon I was told. It was a good day to visit the Museum, not one of my favourite past-times as I am more a ‘history and culture in it’s natural context’ buff. But this is not always possible, especially in respect of the Old Masters, and I was hopeful that some of those Masters were on the menu for this day.

The Hermitage is one of the great and largest museums of of the world; in respect of art, second only to the Louvre. It occupies the Winter Palace, stunning with it’s green and white facade on the banks of the Neva River. It houses over three million exhibits displayed in over 350 rooms, but you also get to view the fabulous rococo, baroque and neo-classical interior which so illustrated the wealth and style of Imperial Russia. It is also synonymous with many of the events leading to the Russian Revolution of 1917, so no visit is complete without rehashing some Russian history. It reminded me vividly of my school history lessons, an endless and dark block which I hated.

The museum was born in 1764 when Empress Catherine the Great bought an impressive collection of artworks from a Berlin businessman. She had purpose-built an additional wing to the palace to house them, and avidly sourced further art, sculptures, curios and libraries during her reign. Catherine was also responsible for the name “The Hermitage”, a name that she had given to her private theatre. Subsequent Russian Tzars added less enthusiastically, but consistently, to the collection until 1881. In that same year, Tzar Alexander II was assassinated, and henceforth the Imperial Families relocated to smaller palaces. The Winter Palace was closed down, rarely to be used apart from large state entertainments or occasional short winter stays by family members. By 1915 it had been transformed into a fully operative hospital for the heavy casualties of the Russian Army in World War 1.

The Winter Palace had become, however, the symbol of the social inequities of Imperialist Russia, and therefore became central to several important historical events culminating in the revolution of 1917. The resulting abdication of Tzar Nicholas II and his execution along with his entire family, by the Lenin-led Red Army, marked the end of both Imperial rule and the Romanov dynasty. The Winter Palace was officially opened and declared as The Hermitage Museum in October 1917, and the public were permitted into the interior for the first time.

Massive damage to the buildings, looting, and the dispersal of it’s treasures elsewhere throughout Russia occurred during the revolution, the early communist years and the Siege of Leningrad, which was the communist-era name for Saint Petersburg. It was not until 1945 that restoration work on the palace began. The city had fared better under communist rule than elsewhere in Russia due to, in part, the local governing commander who was very mild in his Marxist ideologies. Whilst not being able to completely protect the history and culture of his beloved city, he at least managed to prevent the mass destruction of it as had happened elsewhere in Russia. So, with the fall of the USSR in 1991, Saint Petersburg was much better placed for the restorations necessary to showcase the city and the museum towards what it is today.

It is impossible to see everything in one short visit so the decision was made to view the main Staterooms and what was known as the “Hidden Collection”, at the advice of our lovely guide Helena. I mention her here for she still shines as one of my great guides. Her easy, warm and patient nature imparted endless knowledge of both the museum and her city. She exhibited deep pride in her Russian heritage, whilst clearly acknowledging with humour and compassion the problems they were facing in moving forward out of communism. She was a happy consequence of our limiting Russian visas (which did not allow us to roam around unaccompanied at that time), and left me with very fond memories of three amazing days in Saint Petersburg

We made our way through the main entrance and ascended to the first floor by the most beautiful staircase it has ever been my privilege to walk upon. The innumerable staterooms displayed the most stupendous array of riches and lavishness that, in my own experience, was unparalleled to any other great building I have ever visited, (except perhaps Versailles). You drifted in awe from room to room, each a museum-piece in itself, feasting your eyes on the grandeur and trying to absorb the immensity of the excesses of wealth and opulence. In the face of so much extravagance, you could begin to understand the reason for the revolution, considering the average living conditions of the populace at the time.

One of the more memorable rooms was the Hall of Saint George. Larger than a football field, lined with marble Corinthian columns, the Empress Catherine’s throne was positioned splendidly at the far end. The light, balance and spaciousness of the room was exquisite and held an elegance that appealed greatly to me. There was another gallery celebrating the Russian Military. Endless paintings of royals, noblemen and generals in fabulous uniforms, horses and swords, tier upon tier, marched along the red-lined walls. Too many to absorb, too many to count. Entering a drawing room for one of the Empress’s, I was entranced by the malachite columns gracing the walls and matching fireplace. The rich green of the stone against the white walls and gold accents was stunning. There was a gold room and an amber room; can you imagine how they glowed?

Many large, architectural decorative pieces were in solid gold, not just gilt. There were so many different styes of beautiful inlay floors and sumptuously decorated domed ceilings. And then there were the furnishings: fabulous pieces dripping enamels and semi-precious stones, fairy-tale clocks, precious trinkets, sculptures, and painting after painting after painting of the Russian Nobility.

Also very significant in my memory were two extremely beautiful vases. One was about 5 metres long and over 2 metres high and carved out of jasper. Weighing over 19 tons it took more than a thousand men to haul it to the palace. The other was an Italian- influenced malachite vase, soaring up towards the ceiling, exquisitely beautiful.

From the countless sculptures on display, I fell in love with a Michelangelo; the “Crouching Boy”.

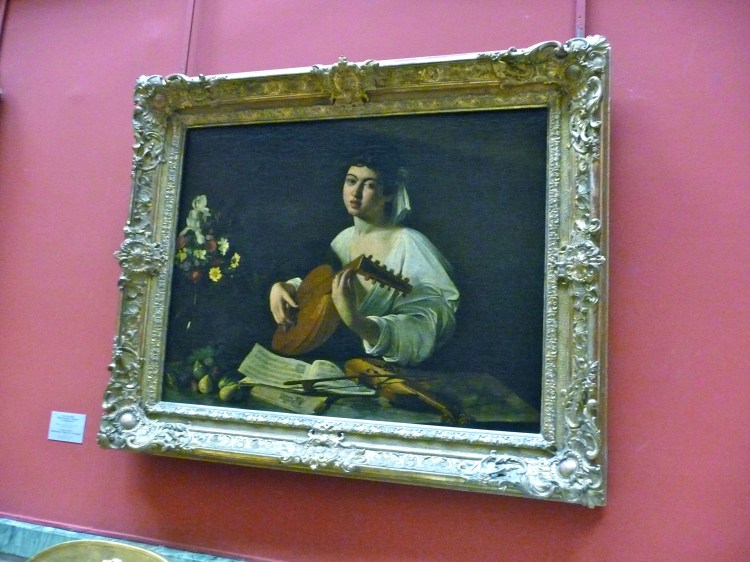

Having gorged ourselves with all this decadent opulence it was time to turn our attention to some serious art.

I have since seen different versions of this story but this is it as Helena told it. In 1993, in the course of renovations deep in the bowels of the palace, workmen noticed that a room they were working in appeared to have been partitioned off. Upon removing this “false” wall, priceless treasures, including 74 unframed Masters, were found stacked up in dusty piles. Later valuation would sit at more than $US262 million and it would come to be known as the “Hidden Collection”.

To go back a little, when the Red Army invaded Germany in 1945, countless treasures were seized from the defeated Nazis and taken back to Russia. These documented treasures, plundered from the bunkers that museums and galleries had hidden during the war, were returned to East Germany in 1958. But the Nazis had also extensively looted the countries they invaded and occupied and it was presumed this “Hidden Collection”, being undocumented, belonged to private individuals. Many of the paintings had, in fact, never been viewed before. For whatever reasons, those involved in bringing them to Russia, had either died or kept quiet, so the treasure was unrecorded.

In 1995 when The Hermitage announced the opening of “The Hidden Treasures” exhibition, it garnered world-wide attention. Various families came forward citing ownership, and whilst some paintings have been returned, other claims are now in the delicate balance of solicitors and governments. But the ownership of many of the paintings is still a mystery, and it is thought that they were most likely owned by Jewish families who did not survive The Holocaust.

Old Masters represented in this collection included Degas, van Gogh, Cezanne, Picasso, Toulouse-Lautre, Gaugin, Renoir, Monet, and Seuret as well as other lesser known French Impressionists. It was truly inspiring to see all these originals, in a small, intimate and uncrowded setting, and there was the added piquancy of the story behind them.

Before we left one more fun fact was added about The Hermitage: the cats that worked there. They were originally imported from Kazan in 1745 by Empress Elizabeth, to control the huge problem of rats and mice in the palace, but also specifically to protect the artwork. The experiment worked! The cats and their progeny thrived, even outlasting the Romanov dynasty, finally meeting their demise in the Siege of Leningrad (no doubt eaten by the starving people of the stricken city). However, new cats were purposefully re-introduced after the war, and today run freely throughout the complex doing the same job as their predecessors. Eldar Zakirov, a Russian artist, was actually commissioned to do a series of paintings celebrating The Hermitage cats and their work.

After all that visual and historical extravaganza, it was time to stroll across the road and board a river boat. The rain had stopped but the sky was still heavy. Cocooned in glass walls to keep out the chill, we relaxed with a glass of wine and drifted along, leisurely admiring stately mansions, gargoyle-laden bridges and ornate lamp-posts with no further commentary. Perfect days end.