Nanggol – Land Diving

If I had ever made a bucket list, attending the Land Diving on Pentecost Island would have been on it. As a traditional culture lover, I was therefore happy to attend this event which coincided with a port call on the only South Pacific cruise I have ever done.

It was a hot and cloudy day. The extreme humidity was causing my camera lens to constantly fog up, which I had never experienced before, and many otherwise great photos were nothing but a gentle blur, which was very disappointing.

I love that the Pacific Islands are always such a sensory experience. Lush, verdant green flora is punctuated by the sharp brilliance of flowers. The natural tones and weaves of the simple buildings and dusty roads, and the earthy smell of the rich soil, makes me feel a wave of calm. There are the pungent smells of animals and humanity, so typical of village life in the tropics. Eyes are dazzled by the brightly, printed clothing that absolutely no one else could wear. I love hearing the music of their ukeles and drums, and their beautifully-toned voices in song. And most memorable are the warm, smiling, brown faces with soft eyes and gleaming white teeth. These are the images that the Islands conjure up for me.

Making our way from the jetty, we walked through the village that stretches out either side of the road, and runs parallel to the beach. It was fairly typical of most Pacific Island villages, if perhaps a little less affluent. The Ni Vanuatu (people of Vanuatu) are mainly of Melanesian descent, and this was noticeably apparent with their finer features and stature, in comparison to their Polynesian neighbours.

The village was busy; everyone was out watching this stream of visitors pouring along their street. A small band played and sung songs of welcome. Ladies in their brightly printed Mother Hubbard-styled dresses, congregated and chatted. Bare-footed children swarmed excitably, or peeped out shyly from behind their mothers’ skirts. Hens pecked and scratched the ground, the odd pig snuffled about, surrounded by clouds of flies, and dogs lay stretched out in the shade. Like all Pacific Islanders, the smiles were wide and welcoming. There was a festive air.

Pentecost Island is relatively untouched by western influences. There are no towns, just a series of small villages, many not even connected by roads. Apart from their kava production, they live a life of self-sufficiency, with their few animals and crops; yams being their staple food. Village traditional life is still strongly governed by “Kastom” (a pidgin word). Orally passed down through the generations, kastom can be very localized, or it can encompass the eighty-plus islands of the archipelago. It infiltrates all aspects of life from magic to politics and almost everything in between. Pentecost was fortunate, in that most early Christian missionaries were tolerant of their traditions. They either looked the other way, or melded them to work with their own ethos, rather than eradicating them, as tragically happened elsewhere. Kastom is therefore relatively pure to this day.

Pentecost’s most famous kastom is the Nanggol, (Land Diving) and it was this that we were here to watch. This event is celebrated each year between April and June. The threat of monsoon has passed, the yam shoots are emerging, and the lianas (jungle vines) used by the divers are full of moisture and sap. The Nanggol is performed, by men as a test of courage and reinforcement of their masculinity, and by adolescent boys as a rite of passage to manhood. When the divers connect with the ground in their fall, they are blessing the soil. The more successful the jumps, the richer the yam harvest. Such a dual event is steeped in ritual.

After leaving the village we followed along a little further before turning inland. Arriving at a grassy basin, both villagers and visitors were spreading rugs on the ground, arranging food baskets and generally settling in comfortably for the afternoon. Precariously perched on top of a high knoll at the far end of the basin, an enormous rickety tower dominated the scene. Around thirty metres high, it was constructed with saplings and branches, all bound together by lianas,

The construction of the tower takes many weeks and is done by an appointed twenty men. These workers undergo purification rituals prior to starting the work, such as isolating themselves, abstaining from sex etc. When the tower is completed, they carefully rake the surrounding ground to remove all hard debris and stones. A village elder is in charge of the diving lianas. It is his responsibility to ensure they are sufficiently pliant, and to cut them into size-appropriate lengths for each diver. Too short and they will bounce back to the tower, too long and they will hit the ground too hard. An unflexible, brittle liana can easily snap and cause death. The towers are still erected in the ways of their forebears, with neither modern tools or techniques used, nor any modern safety measures implemented.

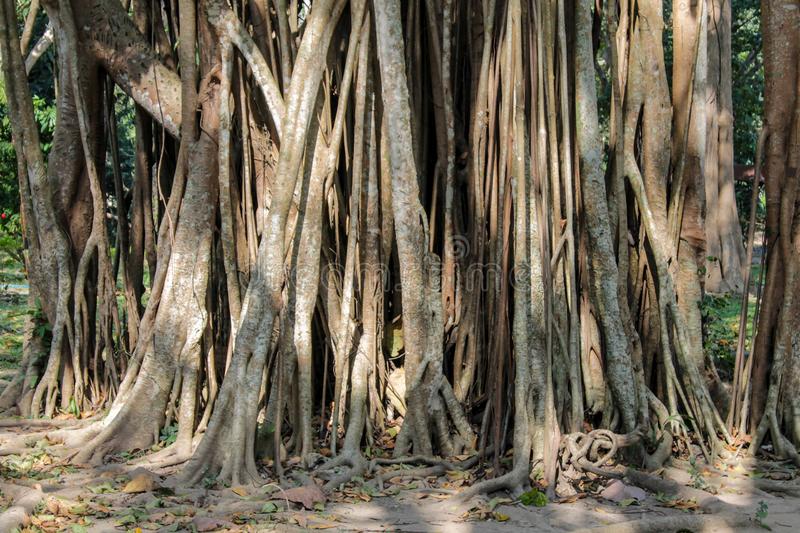

There is irony in the fact that this kastom, filled with taboos against women in every turn, from preparation to performance, actually originates from a clear-headed woman. Legend tells of this woman, running into the jungle, frantically trying to escape her abusive husband, Tamalie. Angrily, he pursued her so she frantically climbed a huge banyan tree to hide in. But he found her and followed up the tree, so at the top she quickly tied a liana around her ankle, and jumped before her husband could reach her. The vine saved her life. Seeing her fall, Tamalie thought she had committed suicide, so in grief, jumped out of the tree himself, and was killed. For the first years, it was the women who were jumping out of trees, honouring the bravery of Tamalie’s wife. In due course however, the village elders felt that the women were shaming their courage and manhood, so set up their own jumps from specially constructed towers, banning women from all further participation. It was also a cautionary tale that no man henceforth be tricked by a woman in such a way again. Over time, subsequent weaving of various kastoms has created the complex ritualistic event as practised today.

I did not come here for a far-away view, so I left the others and climbed the hill to get an on-scene experience. Up close, the tower soared above me and looked extremely unsafe, as though it could disintegrate or topple at any moment.

The performers were starting to congregate now. The divers had all put their affairs in order, as death on this day was a very real possibility. They had slept the previous night curled around the base of the tower, helping Tamalie (who had since morphed into the guardian of the tower) keep away evil spirits. They had undergone purification rituals, anointed their bodies with coconut oil, and were completely naked except for their nambas, or penis sheaths. They were ready!

The women, not permitted to go near the tower as this could cause the death of a diver, had formed lines behind it. They were bare-breasted, and dressed in their long grass skirts, clutched posies of tropical foliage. Swaying rhythmically, they sung songs and performed dances from times immemorial, to honour and bolster the courage of the divers. It quickly became obvious that this was not a show performed for the hundreds watching from the basin below, but a deep and important part of their being, and I felt deeply privileged to be witnessing it.

It was time for the Nanggol to begin. The smallest and youngest boys went first, diving from the lower landings, about ten metres off the ground. Having secured the lianas around their ankles, they stepped forward, crossed their arms over their chests, bowed their heads, tilted forward, and fell. It was quite heart-stopping. Progressively, by age and weight, the dives became higher and higher, culminating with those who dived from the very top, the bravest of them all. These divers can reach speeds of 75 kilometres an hour in their free fall.

Being so close to the base of the tower, it was not just the visual impact of the incredibly dangerous dive, it was the audible one as well. With each dive, you clearly heard the sharp creaking of the tower as it shuddered when the lianas took the weight of the diver. There was the crack of the lianas reaching the end of their elasticity. There was the odd muffled cry from a bad landing. But the worst sound was the thump of the divers hitting the ground with their backs or shoulders. I found it quite distressing. There were moments of anxiety when someone landed incorrectly and the “ground crew” rushed to their assistance. Happily, no one got seriously hurt this day, but there would be some quite serious injuries requiring medical attention on the return to the village, as well as a plethora of torn muscles and heavy bruising.

But for the villagers, this was a successful day. No one had died, so the blessing of the soil was complete. A great yam harvest was assured, and male egos, courage, and proof of manhood were firmly established for another year. I should also imagine that mothers, wives and lovers would privately heave sighs of relief. For myself, I was in awe at the bravery displayed, and the sense of spirituality in the rituals that I had not expected.

But I also felt a sense of intrusion, that I should not be here watching this, uninvolved, as a mere spectator. I think this was accentuated by the fact that I was on the hill among the performers and helpers. There was a palpable collective energy among the Ni Vanuatu; their entire focus was on the ritual. They appeared totally oblivious to the presence of the visitors in their midst. I felt that this belonged to them alone, and should not be cheapened by being turned into a tourist attraction.

This brings about the old argument of the negative effect of tourism on traditional lives and practices. In many cases, unfortunately, it is the money that tourism brings that enables the continuation of maintaining the cultures in today’s world. But we will not go into that. On this particular day I was incensed that, for the first time, permission had been granted for a bar to be transported from the ship, for the use of the visitors. Kastom dictates a total non-alcohol ban for the duration of the Nanggol. On a practical level alone, it is dangerous enough without adding kava to the mix, so I felt that it would not have hurt the tourists to make do with water and soft drinks for a few hours. It would have shown respect for the Ni Vanuatu, caught in the compromise of tradition versus poverty. Save the alcohol for back on board the ship, where, let’s face it, it flowed incessantly. I know I myself, looked forward to a cocktail when I returned, after such a long, hot, and exhausting day.

Back on board, enjoying an exceptional Pina Colada (an indication of how long ago this was), and lamenting my fuzzy photos, I summed up my thoughts about this day. It had been culture-packed; full of song and dance, history and legends, spectacle and courage. I had thoroughly enjoyed it. But I was still touched by the guilty feeling it had been overly commercialised for the cruise. That irritating concept of mega international companies pitted against small groups of poor village elders.

Final fun fact before I leave off. The Nanggol is, of course, the precursor to Bungy Jumping: the idea snitched by some entrepreneurial New Zealander who watched it way back!